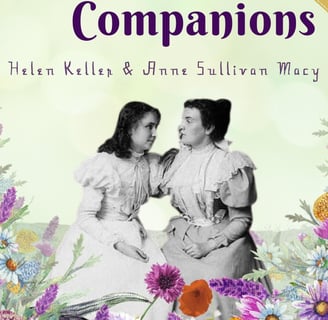

Valiant Companions : Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan Macy (Chapter 1)

This is Chapter One from the book Valiant Companions : Helen Keller and Anne Sullivan Macy, written by Helen E. Waite in 1959 who uncovered previously unnoticed letters of Helen Keller.

9/27/202410 min read

CHAPTER ONE

The Triumphant Day

"NOW just one more things, and you’ll be ready.” Mrs. Hopkins pushed the last ringlet of hair gently into place and stood back to survey her handiwork, first speculatively, and then with approval. "Mr. Anagnos is right—you do look like Miss Frances Folsom!"

Stealing a quick look in the mirror over Mrs. Hopkins' bureau, Annie had a quick shiver of delight. It still seemed miraculous to think that she, who had been practically blind the first sixteen years of her life, could actually see herself in a mirror! Yes, she could see for herself that she did resemble Frances Folsom, the girl who was President Cleveland's bride! Mrs. Hopkins had piled the very dark hair high on her head, and then made ringlets over her forehead with her own curling iron, and in her fine muslin dress with its elbow sleeves and three ruffles edged with lace Annie could have been taken for a bride herself. She wondered if the Bride of the White House could have been more excited than Annie Sullivan was at this moment.

"Now," Mrs. Hopkins said again, and turned toward a mysterious box on the bed. Annie gasped, for out of a bed of tissue paper appeared a wide sash of gleaming pink satin. The older woman's fingers caressed it before she looked at Annie. "It was Florence's," she said quietly. "She wore it at her graduation. I want you to have it—today."

It was like an accolade, for Annie knew how Mrs. Hop- kins cherished all of the possessions of the daughter whose life had been so brief.

"And now I have another girl who's graduating!" Mrs. Hopkins gave the sash a final pat, and nodded approval. "You'll do! Time to go now! Mr. Anagnos wouldn't be pleased if the valedictorian is late."

The feeling of incredulity which had been rising in Annie all day strengthened when they reached Tremont Temple where the commencements of the Perkins Institution and Massachusetts School for the Blind were held. Could she—Annie Sullivan—actually be the valedictorian of this graduating class of 1886? At the steps of the platform her favourite teacher, Miss Mary Moore, smiled at her as she pinned a corsage of pink roses at her belt. Somehow the touch of their petals made her feel faint. Then Mr. Anagnos, Director of Perkins, had taken her hand to lead her to her seat; he was murmuring words of encouragement which blurred in her ears. She was shivering again, and not from joy this time!

The audience! How could she ever face it? So many people! And such famous ones, like Mrs. Julia Ward Howe, the author of "Battle Hymn of the Republic." Mrs. Livermore, an ardent advocate of women's rights, and the Governor of Massachusetts. She sat through the music and the speeches, feeling more and more frozen, her throat tightening by the minute, and then suddenly it was her turn. The Governor looked in her direction with a gracious gesture and announced: "The valedictory—by Miss Annie Mansfield Sullivan!"

Annie managed to rise, but her knees were trembling so that she knew they would never support her! She hesitated so long that the Governor spoke her name again. And then she summoned all her courage to walk toward the centre of the platform. The kindly man led the polite applause, and after a somewhat faint "Ladies and Gentlemen—" Annie was amazed and relieved to hear her voice lifting clearly and easily in the little speech she had written and rehearsed so often. The world was slipping back into focus, and she could meet the interested, friendly gaze of the audience with confidence. She had a quick thrill of triumph. And then she had finished and was bowing to another round of applause, not merely polite this time, but spontaneous and exciting.

After the program her impressions seemed hurried and confused. She knew Dr. Samuel Eliot, one of Perkins' trustees, praised her speech, and Mr. Anagnos was alternately beaming and blowing his nose. "You were a credit to Perkins, my dear Annie, a great credit. And when I remember how you came to us six years ago—"

Miss Moore had no time for anything but a swift kiss, and Mrs. Hopkins couldn't get close enough even for that. But her classmates and the other Perkins pupils crowded around with congratulations, eager to "see" her. With the understanding born of her own blindness, Annie gave them all ample time to let their delicately exploring fingers travel over her dress and her fashionable hair-do, while she laughingly answered their comments and praise. Even Laura Bridgman, the famous deaf, mute and blind member of the Institution was there, as she always was on important occasions at Perkins.

And then it really was over, and she was back in her own little room at school. She closed the door softly. The other girls were still reliving the excitement of commencement, but she had to be alone for her final taste of the wonder and beauty of this incredible day.

Very slowly she unpinned the pink roses and placed them in a glass of water. Reluctantly she unfastened the sash and smoothed it on the bed with loving fingers, wondering if she would ever wear it again. But the dress was certainly her own! How good Mrs. Hopkins, busy as she was with her duties as matron of Annie's cottage, had been to make it for her! She sat on the edge of her bed, touching the tiny buttons as though they were real pearls, and loving the ruffles and lace.

It did require real will power to remove the white slippers—Annie Sullivan owning white slippers! Her eyes darkened suddenly. She was remembering the Annie Sullivan who had come to Perkins six years ago. That Annie Sullivan had been fourteen, practically blind. She had been the most unkempt, untaught, unmanageable—the shabbiest specimen of a girl Perkins had ever received. The only clothing she had had to her name had been two coarse chemises and two calico dresses.

"Annie!" the girls were calling her eagerly. "An-nie!" Annie pretended not to hear. This was a moment she could not share.

Her memories went on. Her first day at Perkins had been a bitter one. The teacher she encountered first of all asked her name and age. She could give that, but when the teacher asked her to spell a word, she could only mumble, "I can't. I can't spell anything!"

"Fourteen years old—and can't spell!" the teacher had never met up with such a condition. She said so, and Annie had sensed her scorn. But worse was to come. The blind girls crowded around the newcomer, felt for her belongings, and then questioned in astonishment:

"Where are your clothes—and the rest of your things?"

Annie had been obliged to shake her head and acknowledge ashamedly that she had none. The girls in the cottage to which she had been assigned had never heard of a girl who didn't possess a coat, hat, extra shoes—even a toothbrush. They said so, and they laughed. And Annie had hated all of them.

"Why didn't your mother make you some things?"

"My mother's dead," Annie had said shortly, "and so's my little brother. And that's all."

Well, it was all the family she would acknowledge. She did have a father, and a sister; but nothing would have dragged the fact out of her that when her mother had died four years before, her shiftless, unreliable father had abandoned his family. An aunt had taken her lovable baby sister, but none of the relatives wanted to be saddled with a nearly blind girl and a small boy with a tubercular hip, so they had been shunted off to the Tewksbury Alms house, one of the most miserable institutions of its kind in the country. The conditions there had killed Jimmie within two months, but Annie had spent four wretched years there until the State Board of Charities had sent Frank B. Sanborn to investigate.

Annie remembered how she had run through the wards the day of his inspection, crying, "Mr. Sanborn! Mr. Sanborn!" and when a man's voice answered her, she burst out desperately, "I can't see very well—and I want to go to school!"

And so she escaped Tewksbury. When she left, one old woman, who had really been genuinely kind to her, cautioned, "Don't never tell nobody you came from the poor-house," and Annie had promised with vehemence, "I won't!"

The teachers and officials knew, of course, but Annie would sooner have died than reveal it to the pupils.

So scantily had she been provided for that the matron of her cottage had to borrow a nightgown for her that first night, and poor, fiercely proud and friend-hungry Annie had cried herself to sleep that night—yes, and for many nights.

When she stepped into Perkins it was almost as though she had stepped upon another planet. Not only did she have to begin her education with the first grade, but she had to learn to live a life she had never known existed. Always the Sullivans had been desperately poor, her mother had always been ill, and life at Tewksbury had been grim. Here at Perkins her schoolmates were fortunate children, despite their blindness; they were children of doctors, merchants, lawyers, prosperous farmers. The girls in Annie's cottage were happy, sheltered girls, and none of Annie's experiences had taught her how to lead a happy, sheltered life.

No wonder she had been confused, difficult and defiant. If she had been an easily defeated person her first year at Perkins would certainly have crushed her, but Annie Sullivan would never be a person to surrender. She had come to Perkins to learn, and learn she did, swiftly, forging ahead to take her place with classmates of her own age. But more than that, she learned at Perkins to seek beauty, and truth and justice.

Perkins had been good to her. Most of her teachers had been kind. They'd clothed her, given her special lessons, stood between her and a return to Tewksbury when her defiance had almost stretched the authorities' patience to the breaking point; had seen that she had free tickets to lectures and concerts. But the thing that she would always be passionately grateful for was that someone had suggested there might be hope for her eyes, and had arranged to have her taken to the Eye Clinic on one of the free days. After that there were two operations, one when she was fifteen, the second exactly a year later, and when they were over Annie could see! Oh, not perfectly—Dr. Bradford had warned her she would never do that, and she must always avoid over-using or straining her eyes, but—she could see! She could learn to read print, see the bricks in a building across the river, and the day she discovered that she actually could thread a needle without using her tongue, she almost died of sheer joy!

She had remained at Perkins after her sight was restored because there really was no other place for her to go. She had earned her way by helping with the teaching and the care of the smaller children, but now—what was she to do now? She knew only too well that thought had been troubling her friends for the past several weeks. Would she—would she have to return to Tewksbury after all? The thought made her throat tighten with fear.

Resolutely she stood up and began putting her dainty things away. The supper bell was ringing. Annie summoned all her courage. She would go down and be as gay and excited as any girl at the cottage, and for tonight no one should guess that she wasn't the happiest girl in the city of Boston.

Perhaps one person did know. One wouldn't have suspected the prim-appearing, typically New England widow Mrs. Hopkins of being a kindred spirit to restless, temper-tossed Annie Sullivan, but as long as Mrs. Hopkins lived there would be a special bond of understanding between them. Now, as the girl descended the stairs, the matron paused in her bustling about the dining-room to smile proudly at Annie.

"You did beautifully, dear," she told her, "just as I knew you would.”

"It took the courage of a thousand Irish chieftains," Annie confessed ruefully, "I was so ashamed when the Governor had to call my name a second time!"

From the end of the table where she was deftly seating her small charges, Miss Moore smiled at her. "We were all proud of you, Annie!" Coming from Mary Moore the words had special meaning, and Annie was doubly grateful. Mary Moore had been the teacher who had given special time and patience to teaching and taming the wilful, ignorant, capricious child Annie had been. Sometimes Annie suspected that Miss Moore knew how to "get her under her thumb" better than anyone else, but she adored her for all that.

"Sit here by me, Annie!" "No, I want her with me tonight!" "Oh, Annie, please come sit by us!" The younger girls chorused eagerly, and anxious little hands reached out imploringly, but Annie gently evaded them all.

"I'm going to sit by Laura, tonight," she announced, and went to take her place beside a stiffly erect, silent woman, whose strangely fixed expression made her a rather weird figure in the midst of this lively group. At the touch of Annie's hand, however, her face lighted instantly, reminding those who could see her of sunlight on rippling waters. She made a series of butterfly-quick gestures in the air, and Annie replied with the same finger-talk in Laura's hand, because for deaf, mute and blind Laura Bridgman the only means of communication with others was this finger alphabet used by the deaf. All the teachers, matrons and pupils could use it, for Perkins had been Laura's home since she was seven. Somehow Annie had acquired a special skill with it, and she was one of Laura's favourites.

Now, seated beside her at supper, Laura began spelling out eager, staccato questions, and Annie answered with flying fingers, describing the goings-on around the table between bites, and promising to go to Laura's own room later to tell her about Commencement.

Commencement had really been a success. The Boston papers even said very flattering things about the valedictorian, which made delightful reading, but did not answer the question that kept nagging at the valedictorian's mind: What was she to do now—what could a girl do, anyway, who would go through life with a painful eye condition and defective sight?

No one had produced a satisfactory solution by the time Perkins closed for the summer, and although Annie smiled and held her head high with an Irish jauntiness, her worry had become a fear that was always lurking in the background of her consciousness and sometimes darted out to give an unexpected jab.

"You are coming to Brewster with me as usual, of course," Mrs. Hopkins had informed her decisively, "and if anything promising turns up, you can be notified in Brewster just as easily as if you were in Boston."

Mr. Anagnos agreed. "She is right, my dear Annie. Quite right. And all the teachers as well as myself have you in mind. We'll let you know immediately, never fear." He patted her hand reassuringly. "Now go and enjoy your summer, my dear."

Annie's lips felt stiff as she thanked him, and her smile was difficult to manage.

She accepted Mrs. Hopkins' invitation gratefully, but she realized this was only a stopgap, and she faced the fact soberly, and when the door of the cottage which that good lady headed as matron (there were several cottages on the Perkins' grounds), snapped shut after them, it had the sound of doom to Annie's ears.

The Perkins Institution and Massachusetts School for the Blind was the only place she could call "home." Was its door closing upon her for ever?